Economic update: The interest rate peak is getting peakier

Summary

- The RBA hiked rates by one quarter percentage point at its June meeting, taking the cash rate to 4.1%.

- Concerns about inflation staying too high is the key concern.

- While I have been thinking rates had peaked, the risk very much is that there are more rate hikes to come.

- I now think the peak cash rate in this cycle will be 4.35%.

The RBA hiked rates by a quarter percentage point at its June meeting, taking the cash rate to 4.1%. Concerns about inflation staying too high for too long was the key factor driving the rate rise. The higher-than-expected April CPI data was probably the most single important single piece of data. But a backdrop of stubbornly high global inflation has not helped. At the start of the year the thoughts were that the cash rate might rise by between one quarter to one half percentage points in 2023. The cash rate has already risen by one percentage point this year, and the RBA may not have finished yet.

There have been good arguments as to why the cash rate should peak at 3.5-4%

For some time I had been thinking that the peak in the cash rate would be 3.6% in this cycle (subsequently revised up to 3.85%). My key argument was that size of the rate hikes (and the speed of the change) matters as much as the level of interest rates. The failure of several US banks and the problems in the UK bond market last year were two examples where the financial system was unable to painlessly absorb the rapid pace of interest rate hikes.

RBA analysis indicates that the full impact of higher interest rates does not hit the economy until 12-18 months following the rate change. And there are obvious reasons in this economic cycle as to why there are delays in higher rates impacting the economy. These include the higher-than-normal proportion of fixed rate home loans, as well as the supply-chain problems and worker shortages resulting in longer-than-usual delays to meet customer demand (notably in residential construction).

Over the next 6-12 months a sizeable proportion of borrowers will have rolled over from fixed home loans to variable rates. While the focus has been on the ‘fixed-rate cliff’ the majority of borrowers are already paying higher mortgage rates. The rise in mortgage rates has not been as steep as the increase in cash rate reflecting tough competition in the mortgage lending market although anecdotally this is changing.

Supply-chain problems are less of an issue, with a fair chunk of the residential construction backlog to be completed over the next 6-12 months. Concerns about worker shortages will continue to decline although may remain a worry for many firms for another 1-2 years.

There are clear signs the economy is slowing. The leading economic indicator series for the economy is declining. Forward orders are growing at around their long-term average although that is well down from the pace seen this time last year. Building approvals point to a sharp slowing in residential construction next year. Household spending on discretionary items is weakening (such as spending at restaurants and cafes). Business and consumer inflation expectations data point to easing pricing pressures, albeit at a level above what is consistent with 2-3% inflation.

The huge amount of saving built up over COVID has allowed some households to keep spending despite the rising cost of living and increasing interest rates. The excess saving is likely to be able to fund spending by a segment of households for some time.

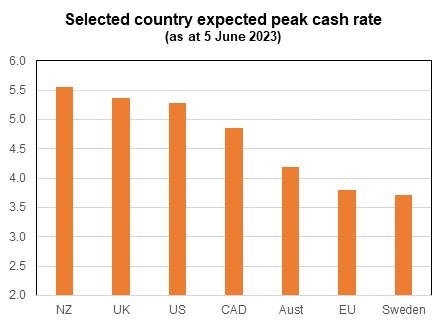

The projected peak in the cash in Australia is not high by peer country standards.

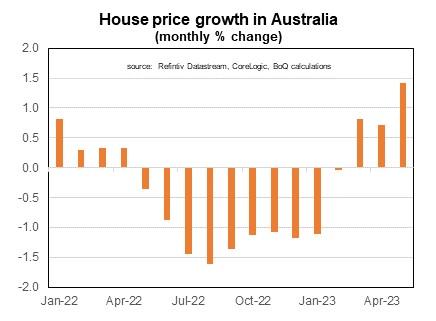

House prices are on the rise despite increasing interest rates.

You can read my full update here.

We really do live in interesting times.

Regards,

Peter Munckton - Chief Economist.